Completing the Cycle

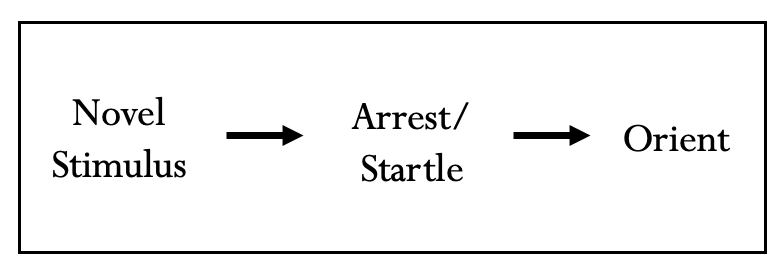

When faced with something new and potentially dangerous in our environment, the nervous system initiates a “threat response cycle.” It’s an automatic and involuntary reaction.

The purpose of this reaction is simply to keep us alive—the nervous system is protecting us.

The threat response cycle features a series of activities, beginning with the “arrest” and “startle” responses. When we arrest, we experience a “mini-freeze,” where we become very still. Picture a squirrel or a deer suddenly pausing their movement when they become aware of your presence.

Almost simultaneously, we experience a quick “jump” in response to the stimulus; this is the startle response. Imagine startling upon realizing you’re about to step on a snake: everything inside you feels like it’s shooting upward.

When we arrest and startle, the sympathetic nervous system quickens a bit. We become more alert and focused. Our heart rate increases and visual field sharpens.

This leads us to the next step of the cycle: orienting.

When we orient, we’re identifying and evaluating a threat. Say you’re walking in the woods and there’s a sudden crash nearby. You’re not exactly sure where the event is happening, so you broadly scan your environment to get a sense of where to focus. You see some movement in the distance, and then narrow your focus in that direction.

You have now oriented to the novel stimulus, first by broadly scanning, and then by zooming your attention toward the site of novelty.

Arresting, startling, and orienting all typically happen quite quickly and automatically. We’re suddenly very attuned to our environment.

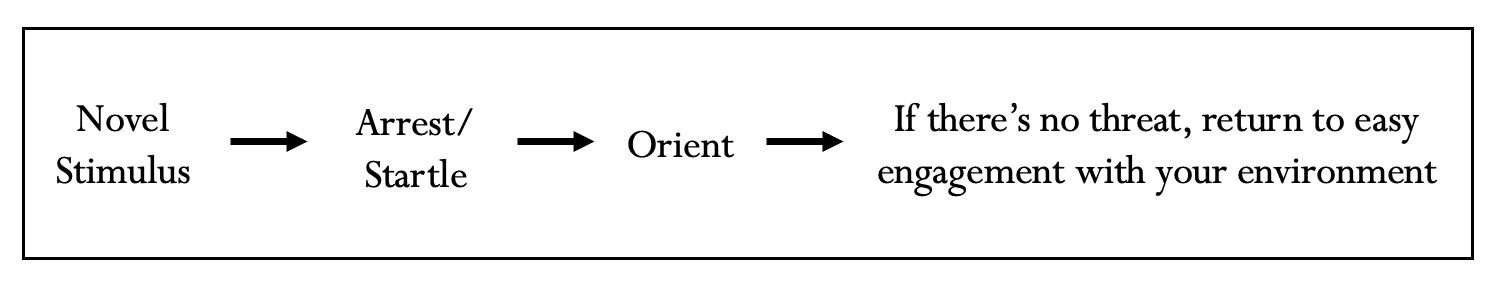

Say the novel stimulus turns out to just be a falling tree branch that momentarily spooked you. Well, there’s no need for the survival response cycle to go any further than orienting, so now your nervous system can simply return to its more easy-going baseline.

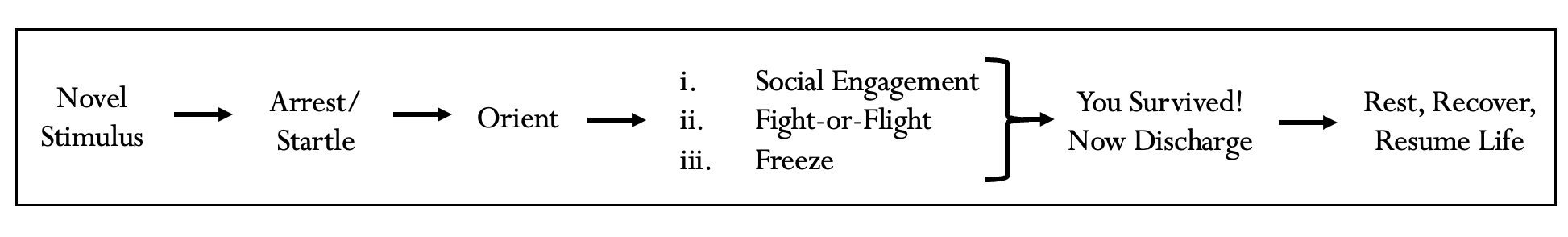

But if there is indeed a threat in your environment, the nervous system now has a choice of three responses to that threat:

(1) social engagement;

(2) fight-or-flight; or

(3) freeze.

If the threat can be navigated by using our capacity for social engagement, that’s certainly preferable, since this demands very little of our internal resources.

Say someone unfamiliar is knocking on my door. I arrest and startle momentarily because I wasn’t expecting anyone. I look out the window and I orient to this person. My nervous system, based on what I observe, determines that the person doesn’t seem overly threatening, so, instead of fighting or fleeing or freezing, I move into social engagement. I open the door, raise my eyebrow, make eye contact, smile, and ask how I can help them. They realize they’re at the wrong door, and I direct them to my neighbor’s home.

No big deal! Whatever mild arousal occurred through arresting and startling settles back down quickly.

However, if the person at my door turns out to be aggressive and attacks me, social engagement probably isn’t gonna help me very much!

So, in this case, the nervous system moves on to the next option: fight or flight. Here, energy floods into my body so I can act with speed and power. I can try to fight off an attacker or flee toward safety (like the antelope in the header image).

So, that’s the second option for our nervous system: Fight-or-flight. It’s

Now, what about those experiences where we’re overpowered or overwhelmed? If the person at my door has a weapon, it might not be best to make any sudden moves. In this case, the nervous system, with our survival as its top priority, might choose the third option: freeze.

“Freeze” comprises a spectrum of responses that are characterized by motionlessness. It’s a form of passive defense. There’s still a lot of “charge” in the system, but it’s stashed underneath a layer of “ice.”

Freeze is valuable for many reasons. In the case of the assailant at my door: Maybe they’ll leave us alone if we’re still and quiet.

***

So, these are our three options when faced with threat:

(1) social engagement (which is enabled by the ventral vagus nerve);

(2) fight-or-flight (enabled by the sympathetic nervous system); and

(3) freeze (largely enabled by the parasympathetic nervous system).

Again, no matter which of the three options our nervous system opts for, the goal is always to survive.

But survival doesn’t mean the cycle is over! There’s one more important step: Discharge.

Once we find safety, we must let go of the harrowing experience. Wild animals are experts at this. When they survive a chase from a predator and find safe harbor, they give themselves the opportunity to “shake off” the remaining survival energy. They literally tremble, sprint, or thrash, in order to create a pathway for discharge.

That gazelle in the header image, upon escaping the cheetah and accessing safety, feels its energetic charge and instinctively frees it.

Once any animal (including us!) releases its pent-up survival energy, they can finally relax. They can rest and recover. They can resume life.

The threat response cycle, shown below, has now been completed. In other words, the overwhelming experience has been digested and metabolized.

BUT…

The problem for us humans is that we can rather easily get stuck in an incomplete cycle. The overwhelming experience remains undigested.

How does this happen?

Well, we experience a threat and we activate the survival energy needed to survive it, but we don’t complete the process of discharging the surplus energy. We focus more on the thoughts and interpretations about the now-past experience than the present-moment feeling of it. Our big brains get in the way of our instinctual response!

So, the survival charge gets stuck in our neuroanatomy and we end up chronically living in survival mode.

This is trauma.

We might feel ramped up, anxious, nervy, reactive. Or we might feel dissociated, flighty, numb, collapsed.

Survival mode is only designed to last long enough to survive the danger. When it becomes our home base, our default mode, then life becomes very uncomfortable. We consistently feel distressed, like the threat is still present, even if, in reality, it’s long gone.

So, we need to learn to allow our nervous system to let go.

This is where somatic therapy comes in. My somatic work is focused on helping your nervous system “remember” how to discharge its survival energy and return to a state of relative ease and comfort.

I help you track your sensations and allow for spontaneous movements. I support you in “getting out of your own way” so that your nervous system can heal itself and resolve trauma.

Your body desperately wants to complete the threat response cycle. It wants to know that the dangerous event is over now. You have the innate resources and intelligence to finally allow your nervous system to let go of the past and start living in the present again.

Header Photo Credit: https://scottwelshbioblog.wordpress.com/2014/11/23/life-environmentbioscience-seminar-2-14th-november-2014-vertebrate-predatorprey-relationships-in-terrestrial-and-marine-systems/